Why Accessibility is Personal to You, Even if You Aren’t Currently Disabled

3 Important Things You Should Know About Disability

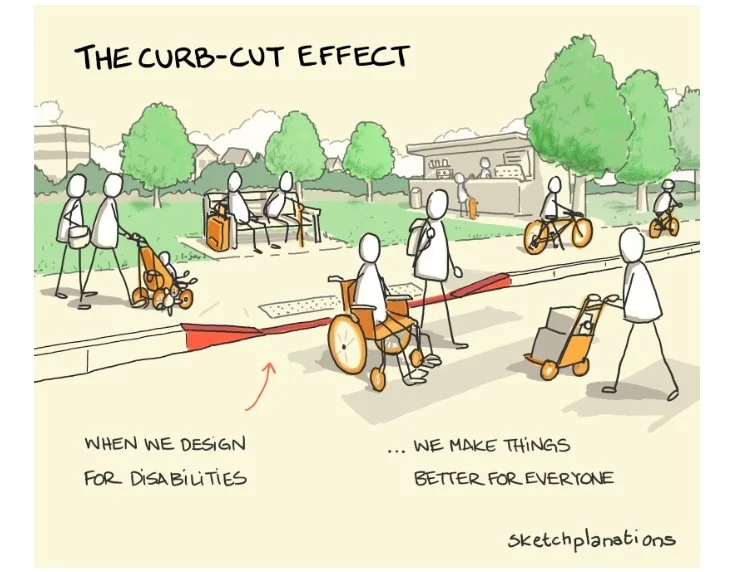

1. Caring About Disability Improves Everyone’s Life

Every time we shift our environment and culture to be more accessible, the entire community benefits. This phenomenon is widely acknowledged as the “Curb-Cut Effect,” a term coined by Angela Glover Blackwell in a 2017 essay of the same name. The basic premise is that when a sidewalk curb is cut into a ramp for wheelchair users, this also makes movement easier for parents pushing strollers, folks dragging luggage, bikers, skaters, etc (basically, wheels ad nauseum). Many “Curb-Cut Effects” you could probably name, like elevators as the standard in modern buildings, and closed captions available on streaming services. Others might surprise you, such as fidget spinners, audiobooks, or Siri, since they started as accessibility tools and were then heavily adopted into mainstream culture.

[Image Description: a sketched street view with stick-figure people using a curb-cut: A person in a wheelchair, a person pushing a handcart stacked with boxes, and a person with a backpack in the crosswalk; two people with a stroller, two people riding bikes, and two people on a park bench on the sidewalk; there is a park and trees in the background. The text on top says “The Curb-Cut Effect”, while the text underneath, with an arrow pointing to the curb-cut, says “when we design for disabilities… we make things better for everyone”. The image credit is by sketchplanations.]

2. Accessibility Means More Than Parking Spaces

As we set the standards for accessibility – widening sidewalks, flattening building entrances, opening doors automatically, increasing the legibility of street signs, and adding park benches – the urban areas that become the most functionally accessible are also socio-economically exclusionary. Disabled adults, who are more than twice as likely to live in poverty as non-disabled adults in the United States, are the first at risk of displacement from a gentrified landscape. The upscale, cutting-edge doctor’s offices aren’t typically the ones accepting Medicaid. The iPhone 4S, which introduced our aforementioned Siri in 2011, was out of the budget for most people receiving Social Security Income that year ($674 a month). State-provided benefits like Social Security Income and Medicaid also come with limits, requirements, and rules for beneficiaries. For example, the income cap means that two people on SSI can’t marry each other without losing their benefits. The ordeal itself of navigating these difficult systems, often described in the disabled community as “death by a thousand papercuts”, has been linked to negative health consequences.

Disabled and chronically ill people also typically face social stigmatization, housing insecurity, a lack of employment opportunities, income inequality, transportation challenges, voting disenfranchisement, and higher rates of arrest, incarceration, and police brutality. Starting in elementary school, kids with a documented disability are 4 times more likely to be arrested than their non-disabled peers. For those who are multiply marginalized (Black, Brown, Indigenous, LGBTQ+, migrant, poor, etc), these adversities are not just compounded but cascade into an avalanche of interrelated struggles. The barriers to equal access isolate actual, complex, entire humans who are disabled, so it’s easy for people to be influenced by the stigmas.

[Image Description: a screenshot of an X exchange. Daniel Lawson, @DanielLaw1998, posted: “Disabled parking should only be valid during business hours 9 to 5 Monday to Friday. I cannot see any reason why people with genuine disabilities would be out beyond these times.” Jennifer Lee Rossman, @JenLRossman, responded: “We’re disabled, Daniel, we’re not werewolves.”]

3. Disability Is An Experience That We Shape As A Society

The truth is that illness and impairment are universal circumstances. They are intrinsic threads of the shared human story, parts of us no door can shut out, no box can keep contained, and no dark, secret eugenics program can eliminate. They do not recognize the boundaries of class, race, gender, or age. Every person can become chronically ill or critically impaired, and almost certainly will as a function of time. “Disability” is the result when an illness or impairment interferes with a person’s ability to engage with or participate in tasks or activities. That may sound simple, and in an ideal world, it would be. But being disabled is situationally dynamic – the reasons a person may be unable to participate have as much to do with how to reach and be in the spaces where the activities take place as with being able to perform the activity itself. There is a movement in the disabled community to adjust our language around accessibility to make it clear when the limitations are coming from an outside social or environmental factor that could be fixed to be more inclusive. These are things that we, as a community, can come together to repair or prevent in the first place.

[Image Description: A list with Istoype-Stype disabled people down the left hand side, saying: “When I can’t Access your Website. You Disable Me. When I can’t Access your Building. You Disable Me. When your Recruitment Process isn’t Accessible. You Disable Me. When your Company Culture isn’t Accessible. You Disable Me. When your Content isn’t Accessible. You Disable Me. We are Disabled by Society.” Image Credit by Linkedin Shieldsjamie]

We make design and operations decisions every day, and, whether we realize it or not, those decisions are choices about who we are welcoming into our spaces. The other side of access is participation: when people can’t read a flyer, enter a building, or get to a part of town, they also can’t contribute their knowledge, skills, or resources. More than a quarter of Americans are currently living with a disability, according to CDC statistics. That’s a quarter of the population not accessing and participating in local education, business, government, etc. The effect of one decision could be limited to a single event or widespread across industries and nations. Therefore, it’s imperative that we consider accessibility in all of our decision-making, listen to disabled community members, and especially include disabled experts in decision-making processes. Doing these things will lead to a more equitable world, and many more Curb-Cut Effects. When we advocate for Disability Justice, we’re advocating ourselves, our loved ones, and our community overall - whether already disabled, or healthy and hoping to live long enough to become so.

Written By: Anna Wille

Further Reading:

“The Curb-Cut Effect” by Angela Glover Blackwell

https://ssir.org/articles/entry/the_curb_cut_effect

“The ADA is the Floor, Not the Ceiling - We Need More” by Kehsi Iman Wilson

https://inthesetimes.com/article/the-ada-is-the-floor-not-the-ceiling-we-need-more

“Economic Justice is Disability Justice” by Vallas et al

https://tcf.org/content/report/economic-justice-disability-justice/

Sins Invalid: Access Suggestions for Public Events

https://sinsinvalid.org/access-suggestions-for-public-events/

Sins Invalid: 10 Principles of Disability Justice

https://sinsinvalid.org/10-principles-of-disability-justice/